Advertisement

Why did Bryan Clark, who managed the anti-Issue 1 campaign last year, have a seat at the table at Columbus Charter Review Committee meetings? Last year Clark, chief policy advisor for Columbus Mayor Andrew Ginther, took a leave of absence from the mayor’s office to manage the campaign against Issue 1, the citizens’ initiative proposing an expanded City Council with district representation.

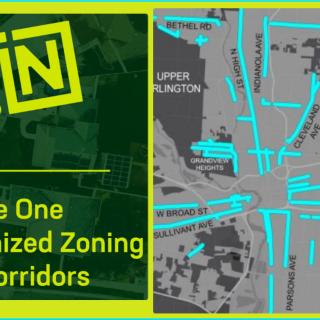

Issue 1 was defeated at the Aug. 2 special election. Many activists believed that Issue 1 lost because of an expensive propaganda campaign by the opposition full of blatant distortion about how large Council would get and the costs to taxpayers if Council expanded.

Clark was among several city employees who made repeated presentations at the Charter Review Committee’s 12 meetings. He was continually at the table in front of them to answer questions and make comments. He and J. Edward Johnson, city council’s director of legislative affairs, were so involved with the committee’s final recommendations that one member suggested calling it “The Clark-Johnson Plan.”

The final Columbus Charter Review Committee meeting on February 16 concluded with recommendations to expand council from seven to nine members and to divide the city into nine districts. Candidates for a district seat would reside in the district and run head-to-head in the primary election.

This sounds like a positive and democratic concession to the Issue 1 citizen proposal. The purpose of district, rather than all at-large Columbus City Council representation, was intended to give more voice to citizens in underserved areas of the city. But, the Charter Review Committee negated the benefits of that idea by adding to their recommendation that all candidates would run city-wide campaigns in the general election.

This setup would provide a district’s residents with the appearance of a council member responsible for their area. Citywide general elections, however, mean that candidates would still need major funding from moneyed interests, estimated to be at least $250,000. And council members would continue feeling great pressure to do their bidding.

The recommendation essentially will allow wealthy funders of the city’s political campaigns to keep controlling City Hall. Under Columbus’ present system of electing all seven city council members at-large, members turn to lobbyists, developers and large businesses for the substantial funds needed to campaign citywide.

Those problems could be alleviated by district elections, which exist in virtually every other large U.S. city. Candidates running solely in a district have lower campaign costs and less need to rely on big-money donors. But the committee was seemingly designed to prevent district elections from being proposed and threatening the power of wealth.

The deck stacking of the Charter Review Committee began with selecting the nine committee members by the mayor and city council, who overtly oppose both district elections and limits on campaign contributions. After at least 40 people applied to be on the committee within the original application deadline, city officials extended it by a week. Most of the persons chosen had applied during the extension, without which city officials would have had to select a largely different group.

A next step involved selecting the persons to make presentations before the committee. All but two were city employees working for Columbus officials opposed to district elections. The exceptions were an OSU law professor who spoke about possible legal challenges to drawing district lines, and a state representative who discussed the history of Columbus' council structure.

The presence of members, presenters and staff who were uber-friendly with city officials, resulted in the committee failing to address recent scandals at City Hall and possible changes to council to prevent similar corruption. For example, they didn’t mention the city contractor Redflex or its corrupt lobbyist, John Raphael, who is in federal prison for pressuring the company to pay what it thought were bribes to the campaigns of Council members and the mayor.

The committee was silent about Council approving the use of over $250 million to acquire public ownership of Nationwide Arena after voters had five times turned down public funding for an arena. Many citizens saw this unconscionable corporate welfare as clear proof that the present Council is more responsive to wealthy interests than to voters.

As for whether at-large elections provide adequate representation for minorities, the committee said nothing even after the state representative pointed out that Columbus’ present system excluded African Americans from council for 55 years. The committee similarly was unconcerned that the at-large electoral system has produced one-party rule in Columbus and a lack of checks and balances on council.

Moreover, the committee didn’t bring up problems such as the city’s 21 percent poverty rate, its infant-mortality rates in some neighborhoods being over twice the countywide rate or its ranking as the nation’s second-most economically segregated large metro area. Nor did they say anything about the city’s sharp increases in homelessness in recent years or its unfavorable ranking compared to other large cities regarding upward social mobility of those born in poverty.

Stefanie Coe, the committee’s chair and a member of Ginther’s mayoral transition team last year, did say when the committee began deliberating on what to recommend: “Things are going well. We. . . have had good success as a city.” Member and former Columbus city councilperson Jennette Bradley added: “It’s a well-performing city,” and, “It is working now. The citizens seem to be satisfied.”

None of the members disagreed with those rosy assessments. They went on to recommend changes to give areas of the city a feeling of representation, while keeping real power with the super-rich who now wield and abuse it. The committee was set up and operated such that any other outcome was virtually impossible.

Joe Sommer is a Columbus attorney and activist who is retired from Ohio’s state government.