Advertisement

On January 22, 2021, Tom Brokaw rendered his resignation as reporter at NBC News, where he had been for the last fifty-five years. He closed out his stellar career at NBC as the only newsman to have anchored all three of its biggest news shows. At the time of Watergate, he was a young thirty-one years old–so young that some in the trade grumbled that he was not experienced enough for the posting–and had been named the White House correspondent for the network. The Fall of Richard Nixon is his experience of the debacle.

The story began with the June 17, 1972, break-in at the Democratic party’s headquarters at the Watergate, a complex of luxury apartments, stores, and offices. Nixon was running for a second term, and he was determined to ensure that his victory was not the nail biter of 1960 or the close shave of 1968. It wasn’t enough to be ahead in the polls; he had to annihilate Senator George McGovern and the Democratic party. He whipped McGovern like he stole something, winning every state but South Dakota, McGovern’s home state, and collecting ninety three percent of the votes in the Electoral College. It would seem to most people that he could relax at bit; he was finally, irrevocably at the peak of the summit. Unfortunately, that was not enough for Nixon.

Frank Wills, a young African American man, was the security guard on duty that night at the Watergate Hotel. While making his rounds, he noticed that the lock on the door to the Democratic party’s headquarters had been covered with duct tape. He removed the tape, but thirty minutes later he found the same thing. Wills called the police, and five men–Virgilio Gonzales, James W. McCord, Jr., Frank Sturgis, Eugenio Martinez, and Bernard L. Baker, were arrested. All five were tried and convicted of conspiracy, burglary, and conspiracy to violate federal wiretapping laws. They were sentenced by Judge John J. Sirica, who was nicknamed Maximum John for the severity of the sentences he handed down. Those sentences were enough to start the defendants talking, during which they confessed to being members of a “dirty tricks” squad for the Committee to Re-Elect the President, thereafter referred to as CREEP. And so began the two-year saga known as Watergate. Frank Wills enjoyed a brief period of fame and played himself in the 1976 film All the President’s Men. His role in the pageant of Watergate, however, has been all but forgotten. He died in September of 2000.

We have to remember that Watergate happened at a time when there were no cell phones, FAX machines, or internet. (That sounds quite blissful now.) The twenty-four-hour news cycle did not exist. The lowly and the powerful got their news in the same way and from the same sources: the three national news networks, and the morning and evening papers across the country.

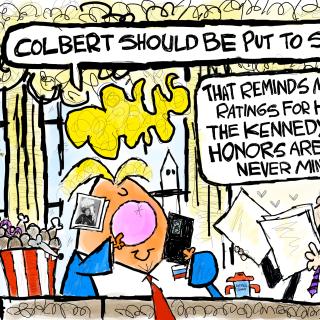

Brokaw shows us a more genteel world in which most reporters respected the profession and each other. They were not above helping out their colleagues with information. However, we do not get a good sense of the very combative relationship Nixon had with the press. This played out during my senior year in high school, and I remember a more irritable, sarcastic, and rude Nixon than Brokaw portrays.

Nixon took to traveling overseas to escape the stench of Watergate and burnish his credentials as a peacemaker. He also generally received more favorable press coverage aboard.. He had barely been home from a 1974 trip to Egypt and a meeting with Anwar Sadat, the president, when he decided to travel to the Soviet Union and try to broker a deal with Leonid Brezhnev, on arms control. .

Brokaw does a good job of showing us that there is little glamour in the job of the White House correspondent. His descriptions of the press’ accommodations and working conditions on the road are far from what much of the public assumes they would be. For Brokaw and a number of other members of the press, it was their first trip to Moscow. He described the main hotel for foreign visitors as a down-on-its-heels army barracks, hardly what one would expect to find in such an important city. “The ancient capital was a dreary, joyless city with a permanent overlay of foul air and cheerless citizens hurrying through the streets with their heads down,” writes Brokaw. Moscow’s central television station was “another dusty building with cracked windows and floors caked with dirt.” The city itself was barely lit so as to save on electricity. The food was dreadful, but the caviar the crew managed to obtain was quite good.

Brokaw passed on the opportunity to harshly criticize Nixon as many other books have. Instead, at the end of the book, he tells a light hearted story of a video his staff put together in honor of his fiftieth birthday. There was a dapper Richard Nixon, sending best wishes and lauding Brokaw’s good judgment! Richard Nixon had pretty much succeeded in rehabilitating himself.

The author gives the reader a just-the-facts-ma’am retelling of Watergate and the first resignation of an American president. The book, however, lacks a sense of drama about the time period and the event. There are also a few factual errors that misrepresent Nixon and those of his administration. These will probably not be noticed by the casual reader or someone who knows little about Richard Nixon.

The Fall of Richard Nixon is a serviceable account of Watergate, and an interesting walk down memory lane, but somehow I expected better of the venerable Tom Brokaw.