Advertisement

In 2020, following the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, local activists were pressing Columbus City Council to pass policy which would rein in one of the nation’s worst law enforcement agencies when it comes to excessive and unwarranted use of force. (If still in doubt, here’s Free Press editor Bob Fitrakis’s article from 2017.)

A few activists back in 2020 told the Free Press they had been promised by Columbus City Council president Shannon Harding that culture-changing policy would be passed. And some policy was enacted, such as a Civilian Review Board and ending the use of tear gas to disperse peaceful protestors.

But the Ohio Coalition to End Qualified Immunity (OCEQI) believed those measures weren’t enough, and that the only policy that would force serious culture change was ending qualified immunity. The legal doctrine that allows public officials to escape consequences (such as being sued) for unreasonable behavior even when they violate someone’s Constitutional rights.

The OCEQI – which was inspired in part by the 2017 Columbus police murder of Kareem Ali Nadir Jones – has worked countless hours and spent tens-of-thousands trying to put their “Protecting Ohioans’ Constitutional Rights Amendment” on a statewide ballot to allow Ohio voters to make their own decision on whether to end qualified immunity. Sounds like democracy in action, but Ohio Attorney General and Republican David Yost blocked their proposed amendment five times since the beginning of 2023. With each rejection, Yost argued the summary language of OCTEQI’s ballot initiative was misleading to voters.

Not long after Yost’s latest rejection the OCTEQI filed an emergency motion with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Cincinnati, and on Wednesday a three-member panel from the court ruled 2-1 that AG Yost must stop blocking their amendment and certify its summary language. This federal court is heavily conservative, as eight of its 11 judges were appointed by Republicans. The three-member panel essentially ruled that Yost was violating the First Amendment rights of the OCETQI.

“We feel validated the court ruled in our favor because we were right all along when Yost said we never changed our language. But each and every time he denied us, our legal team would go and address his concerns,” says Cynthia Brown, the aunt of Kareem Ali Nadir Jones, and spokesperson for the OCTEQI.

AG Yost said he will appeal this latest ruling in the same federal court.

In the meantime, “Protecting Ohioans’ Constitutional Rights Amendment” will be forwarded to the GOP-dominated Ohio Ballot Board, which is tasked with approving the actual ballot language voters will make a choice upon.

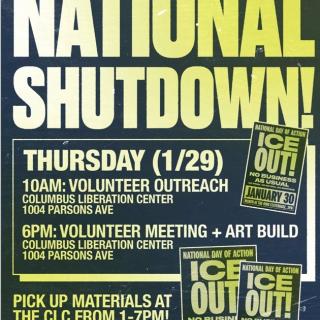

If approved, and if the amendment survives Yost’s appeal, the next step for the OCTEQI is daunting for any statewide citizen-led ballot initiative. Collect 412,000 signatures from valid voters, and make sure these signatures are represented from at least 44 of Ohio’s 88 counties.

According to a poll taken in April by Campaign Zero, which helps fund the OCETQI, 87 percent percent of Ohioans believe that officers should face consequences for violating a person’s rights, and 53 percent percent of Ohioans believe qualified immunity should be eliminated. Four states – Colorado, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, and New York City – have completely banned police officers from using qualified immunity as a defense in state court.

Initially introduced during the civil rights movement, qualified immunity was meant to protect law enforcement officials from frivolous lawsuits and financial liability when they acted in good faith in unclear legal situations.

Over time, however, courts increasingly applied the doctrine to cases involving excessive or deadly force by police, leading to criticism that it has become a nearly failsafe tool to let police brutality go unpunished and deny victims their constitutional rights.

By ending qualified immunity, OCTEQI seeks to hold the state and its political subdivisions accountable for the conduct of their employees and ensure responsibility for any constitutional rights violations.

The OCTEQI’s mission is to end qualified immunity, address systemic racism, inequality, and injustice, and rebuild trust between law enforcement and the community, says Brown.

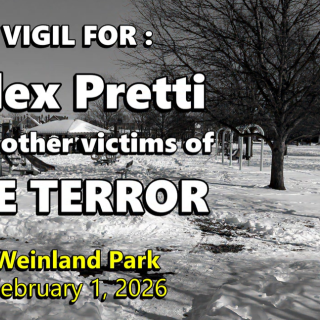

If all goes to plan, the OCETQI amendment could appear on a 2025 or 2026 ballot, she says. As mentioned, the OCETQI has worked relentlessly to raise awareness and gather signatures to have AG Yost move the their proposed amendment past its initial hurdle.

“We have been to over 50-plus counties gathering signatures. I want to thank the tens-of-thousands of people throughout the years who have signed the petition, agreeing that qualified immunity should be ended,” said Brown.