Back in October at the historic federal opioid lawsuit in Cleveland, Cardinal Health and other opioid distributors were several hours away from opening statements. But then a settlement was reached by two Ohio counties, Summit and Cuyahoga.

Outside the courtroom waited several parents who’s pain pill addicted children had moved on to heroin and overdosed. The settlement was another bitter blow as they seek closure. Because it meant Dublin’s Cardinal Health and others made no admission of wrongdoing.

The Summit and Cuyahoga County’s case was a bellweather trial which will lay the groundwork for hundreds of other cases across the country.

The two counties settled for $260 million. The Free Press did the math: The CEOs of the companies that settled had a combined annual salary of $66 million in 2018. Thus the total settlement amount is equal to four years of these CEO’s annual earnings.

And as the federal trial moves forward, many more plaintiffs (such as Franklin County) will also probably settle. Meaning Cardinal Health, with annual revenues exceeding $130 billion per year, will not have to answer to why they helped push 76 billion pain pills on America between 2006 and 2012.

Thus the distributors are turning their backs on grieving parents, and in many ways, telling them this is all you and your dead child’s fault.

Instead of selling out, the plaintiffs – again, mostly local and state governments – should force a trial. To make Cardinal Health and others squirm under the overwhelming evidence they are to blame for this epidemic which by many estimates has taken the lives of 400,000.

If you have physical or emotional pain, your ability to make choices is disaffected and you’re probably going to seek immediate gratification, says Columbus-based chemical dependency counselor Tony Anders.

“If you have a magical pill that will take your pain away, I would say, ‘sign me up,’” says Anders who, after a car accident, overcame an opioid addiction himself before becoming a therapist. “I have asked hundreds of people who sat on my couch, ‘How many of you, ever since you were four years old, said I want to grow up and do something that destroys my life and the collateral damage will take my entire family down?’ Nobody has said that. Ever.”

Anders contributed an essay in the recently published book, “Not Far From me: Stories of Opioids in Ohio”. His chapter “What Addiction Gave Me”, talks about how his addiction resulted in him having greater compassion. Before being prescribed pain pills following his car accident, Anders owned a hair salon which he lost.

No surprise is how Cardinal Health and other distributors are lacking true compassion when they refuse to admit they played a huge role in this epidemic.

As unbelievable as this may sound, during the federal opioid trial, Cardinal Health and other distributors essentially told the federal government you are to blame. Or you should have stopped us, considering the distributors from 2006 to 2012 were self-reporting to the DEA and FDA the number of pills they were shipping out.

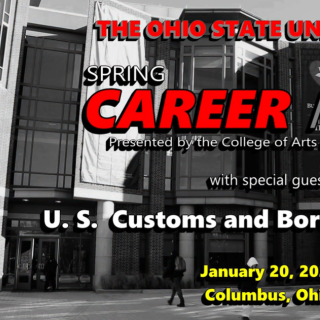

Which begs the question: Is the federal government settling with Cardinal Health and others because they too knew the number of pain pills being distributed was leading to a lost generation and did nothing to stop it?

“What Cardinal Health will say is, ‘It’s not our job to question what physicians are prescribing.’ They are tapping into this narrative that nobody should be overruling the doctor-patient relationship,” says Ohio University associate professor of health policy Daniel Skinner. “But when you have millions of pills be distributed to a town of a couple hundred people, somebody has to sound the alarm. Certainly, Cardinal Health has culpability, but also there’s part of it that’s right about the DEA and FDA. There’s enough blame to go around.”

Skinner is the brainchild of “Not Far From me: Stories of Opioids in Ohio”. He says at the end of the day a settlement is a way for Cardinal Health to keep this out of the news and as quiet as possible.

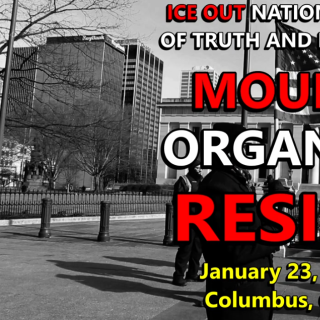

“We are going to have nothing like a truth-and-reconciliation commission around this,” says Skinner. “We are used to this as Americans where power brokers don’t do jail time. But at the same time most people understand the fundamental unfairness. Their children are dead and the CEOs are on their yachts.”

If the settlements are used properly, Skinner suggests hopefully they will have a lasting impact.

“We have the enduring results of a massive crisis that’s going to take generations to address. So somebody has to pay for this and the public health systems in Ohio don’t have that kind of cash.”