Advertisement

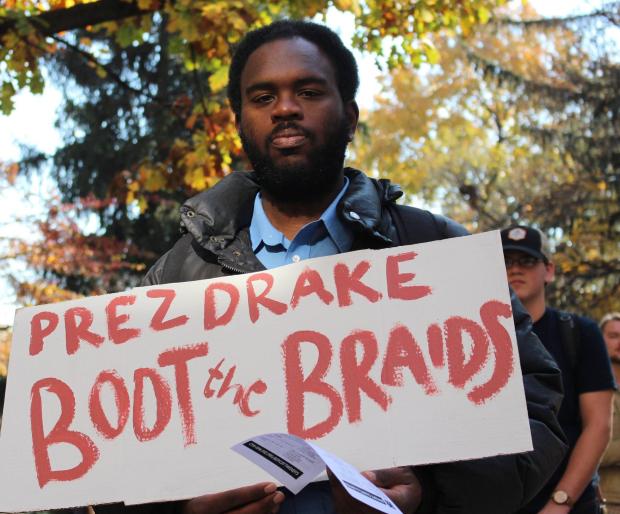

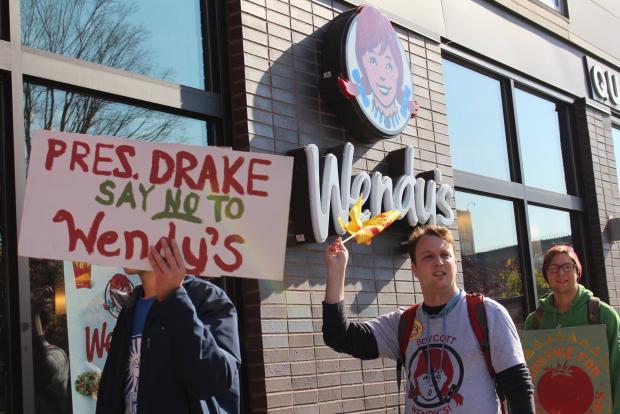

The Student/Farmworker Alliance held yet another protest on the Ohio State University campus on November 15. The student organization is engaged in a protracted struggle with OSU that began in April 2014, when they asked the university to terminate its contract with the Wendy’s Corporation. The fast food chain operates a restaurant in OSU’s Wexner Medical Center.

At issue is the human rights of farm workers in Wendy’s supply chain. Wendy's has refused to join the Fair Food Program developed by the Florida-based Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW). Joining the Fair Food Program would alleviate the poverty of farm workers who harvest the fresh tomatoes used in the Wendy's sandwiches and salads. The CIW's program also promotes a safer, more humane working environment, including zero tolerance for sexual harassment and slave labor — abuses still common in the agricultural industry.

The Student/Farmworker Alliance (SFA) held several protests in 2014. They met with senior vice president of administration and planning Jay Kasey, chief financial officer Geoff Chatas, and other administrators who report directly to University President Drake. They argued that continuing to do businesses with Wendy’s would make OSU complicit with the roadblock that Wendy’s presents to the expansion of human rights to thousands of more workers.

After these talks, in January 2015 OSU administrators signed an agreement with SFA, promising that OSU would only renew its contract with Wendy’s if the company joins the Fair Food Program, or finds a way to ensure worker rights that is just as good.

Instead of offering a better plan, Wendy’s has tried to skirt the issue by sourcing its tomatoes outside of Florida. “Following the implementation of the Fair Food Program in Florida’s tomato fields, Wendy’s shifted their purchases away from participating farms committed to respecting farm worker human rights to farms in Mexico, where oversight is effectively non-existent,” said Oscar Otzoy of the CIW.

One of Wendy’s sources for tomatoes is Bioparques de Occidente, an agribusiness giant in Mexico that was the subject of a major slavery prosecution in 2013.

Meanwhile, nearly two years after signing an agreement with SFA, OSU has not made a decision whether to renew the Wendy’s contract, which was up for renewal in December 2016. SFA met with administrators again in October.

“They said that they had decided to temporarily extend the contract for another six months,” said SFA organizer Ben Wibking. “They said they had been in contact with Wendy’s headquarters, and were looking into Wendy’s claims about its own code of conduct. They are considering whether Wendy’s internal auditing procedures are just as good as the Fair Food Program.

“They should have done this already,” Wibking said. “We don’t think it should take them a six-month investigation to determine that Wendy’s claims look good on paper, but really aren’t backed up by anything.”

Workers have a voice in the Fair Food Program. The Fair Food Standards Council independently monitors working conditions in the fields and investigates workers’ complaints. If Florida growers fail to resolve legitimate complaints, then companies who participate in the program — such as Taco Bell, Burger King, and Chipotle — will no longer purchase tomatoes from them.

“It can’t be as good as the Fair Food Program because workers aren’t involved,” Wibking said. “There’s no complaint process, there’s no worker-to-worker education about their rights.”

Ultimately it comes down to what OSU values more: human rights in the agricultural industry, or a lucrative contract with Wendy’s.

SFA is also supporting a nationwide boycott of Wendy’s. Student activists have been engaged in the struggle for farm worker rights since 2005, when Taco Bell became the first food retailer to join the Fair Food Program. Canceling university contracts and a boycott were key leverage points with Taco Bell.