Advertisement

Every time there is a solar eclipse that affects Ohio, the old story of Tecumseh’s alleged eclipse predictions of 1806 and 1811 is recycled. Often, some historian attempts to correct the popular myth by saying that it was not Tecumseh, but his brother Tenskwatawa, “the Shawnee Prophet,” who predicted the two eclipses, thus building the cult that regarded Tenskwatawa as a genuine shaman, rendered into the English title “Prophet. “The Shawnee Prophet’s movement did spread, largely on the myth of the eclipse prediction, becoming a major basis of modern syncretic Native American religion. The myth of these “prophecies” has been greatly amplified by the novelist Allan Eckert, whose highly-fictionalized outdoor drama Tecumseh still plays in Chillicothe, Ohio, using the prophecy motif to turn Tecumseh into a Jesus figure.

To de-fictionalize these events, realize that the usual historian’s correction is really incorrect, because the Prophet’s religious movement was just an appendage to Tecumseh’s political effort to build a large Native alliance. That alliance went to war against the Americans in 1811, on the back of two other mythical predictions – another solar eclipse in September of 1811, followed by the New Madrid Earthquake, which began on December 16, 1811.

These myths are easily explained by the lack of evidence that Tecumseh predicted either of them in advance. Certainly, Tecumseh did go around saying that he had predicted the eclipse and the earthquake after they happened – the kind of retrospective prophecy for which the Prophets of the Hebrew bible are infamous. I predict that the NY Mets will win the World Series in 1969. Call me a Prophet.

The Prophet’s prediction of the eclipse on June 16, 1806, is in a different category. At that time, the movement of Tecumseh and his brother was still small and was pretty much limited to the assembled community in Greenville, Ohio, after most of the Shawnees had been forced to surrender their other Ohio lands. As far as historians have been able to reconstruct it, the Prophet’s reputation did grow phenomenally because he was able to predict the eclipse before it happened.

The 1806 “prophecy” began with a challenge from William Henry Harrison, then the general charged with putting down Tecumseh’s movement. Harrison dared the claimed Shawnee Prophet to prove his divinity “by stopping the sun or moon,” or some other comparable miraculous feat. The record of that challenge negates the possibility that the Shawnee simply invented the prediction after the fact.

In response to the challenge, Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee Prophet, is said to have uttered: “Fifty days from this day there will be no cloud in the sky. Yet, when the Sun has reached its highest point, at that moment will the Great Spirit take it into her hand and hide it from us. The darkness of night will thereupon cover us and the stars will shine round about us. The birds will roost and the night creatures will awaken and stir.”

But those are the words of the novelist Allan Eckert, not the Shawnee Prophet. What Tenskwatawa actually said we do not know. There is excellent evidence, however, that Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa did know that the 1806 eclipse was coming, to the day, and they used that knowledge to poke Harrison in the eye, as it were.

Debunking of the myth of prophecy begins with realization that Greenville was outside the path of total eclipse, meaning the eclipse could not have been seen by the Natives assembled in Greenville. (Outside of the zone of totality, the sun still shines sufficiently to prevent looking directly at it.) The Prophet had failed to produce the darkness he said would strike his movement’s capital. The map is from Eclipse Chasers and is based on the NASA map of the 1806 eclipse. The red line represents the central path of totality and the green line is the edge of totality. The totality path of the 1811 eclipse was even farther north than the path of the 1806 eclipse, also missing Greenville. Map 2 is the NASA map of the 1811 eclipse path.

Understanding what happened depends on realizing that the historians’ correction is likely wrong. It was Tecumseh who predicted the eclipses, not his brother. Throughout his life, Tenskwatawa (pictured) was known as a slow-witted drunkard, and the eclipse prediction represents an attempt by his brother to boost his brother’s reputation. Even the spiritual name Tenskwatawa was a false front; he had been called Lalawethika from childhood, a derogatory name that literally means “noise-maker.” We can bet that it was Tecumseh who told his brother about the coming eclipse.

And that was knowledge that Tecumseh likely had without resorting to magic or divination. In the 1790s, Tecumseh had befriended a white man near Xenia named James Galloway. Galloway's daughter Rebecca became Tecumseh's tutor in English and various fields of science and technology. The Galloways almost certainly had a copy of the Old Farmer's Almanac, which began including the schedule of coming solar eclipses in 1792, meaning that this was big news just at the time that Rebecca was tutoring Tecumseh in 1805. If not from Rebecca, Tecumseh could have acquired a copy of the Old Farmer’s Almanac numerous other ways, even as a gift from missionaries or Indian agents.

It’s a safe bet that Tecumseh learned of the coming 1806 eclipse from the Old Farmer’s Almanac, and then told his brother, with the intent of building the kind of religious movement needed to bring tribes into alliance for a rebellion. Of course, the eclipse predictions of the 1790s and 1800s were not very accurate as to path of visibility. That the path missed Greenville supports that the “prophecy” came from the almanac.

Another suggestion that the 1806 eclipse was not seen automatically by the Algonquian tribes as some great spiritual happening comes from newspapers of the time. A newspaper in Louisville, Kentucky, reported that Indians in the totality zone in Kentucky began furiously shooting their guns at the total eclipse to make it go away, or perhaps to make holes in whatever was covering the sun.

And this was not the only case where the novelist Allan Eckert invented a problematic fiction. Eckert dramatized that Tecumseh, already married, actually asked for Rebecca Galloway’s hand in marriage, when Rebecca would have been only 14, in 1805. This remains a great libel about the celebrated Native leader. Portraying the relationship between Tecumseh and Rebecca as romantic blocked Eckert from seeing that the girl was actually teaching Tecumseh about things like eclipses.

This case is very similar to that of the infamous Sirius Cult of the Dogon of Mali. For most of the 20th century it was believed that the Dogon had some kind of mystical knowledge of the star Sirius, which suggested that they had invented the telescope in ancient times or had access to magical intuition. It was then learned that their knowledge of Sirius had come from a band of French astronomers who had visited them in the 19th century, tracking a solar eclipse.

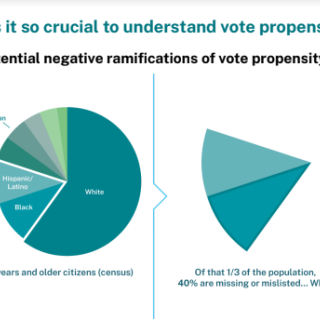

If you don’t think that politicians use religion to build their following, read the newspaper. Some go as far as selling bibles. That Tecumseh actually succeeded with this ruse and did build a religious movement that still has reverberations in the Native community is testament to his great political skill and intelligence. But if you think it was magic, I ask you to refrain from voting in 2024.

----------------------------------

Geoffrey Sea is a historian and writer and administrator of the Adena Core Facebook group.