The historians are coming.

Across the country, untold millions have suddenly awakened to the historical significance of various and sundry statues honoring the great Confederate generals of the Civil War. While their energy is no doubt commendable, their newfound knowledge has not yet permitted them to draw a distinction between education and glorification.

Our newly minted annalists, while wrong-headed, are not necessarily wrong. Although these triumphant monuments are somewhat misleading about the war’s outcome, they are quite informative about the Jim Crow era in which they were built. They also provide renewed motivation for debunking the “lost cause” historical narrative that has convinced generations of schoolchildren that the Civil War was fought by noble southerners over some obscure federalism issue.

Work worth doing, although it does seem an obvious point that Bobby Lee and Jeff Davis were despicable, murderous individuals who caused the death of 620,000 Americans for the sole purpose of keeping human beings as slaves. Tenured college professors get paid fairly well to make this observation, of course, and I don't wish to take bread off of their table – I'm just a music columnist.

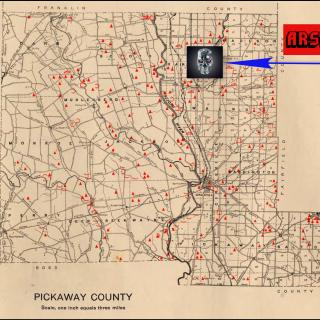

In addition to smashing myths, though, we might take a moment to celebrate some forgotten heroes – the Grand Army of the Republic. In the early 1860s, 313,180 Ohio boys went to war to end slavery, including 5,092 free African-Americans. 35,475 of them would never see their homes again, having been bayonetted at Shiloh, shot down at Cold Harbor, starved to death at Andersonville Prison, and drowned on the Sultana.

There was no question in their mind that this bloody slaughter was a crusade to end slavery. You need look no further than the songs the Union Troops sang in music halls and while they marched to battle. What follows is a small selection.

John Brown's Body (unestablished). An early marching song of the Union Army, this tune celebrated John Brown, the militant abolitionist who tried to arm slaves by capturing the arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia in 1859. Brown was later executed by the State of Virginia, and although his body lies “a-moldering in the grave,” his “soul is marching on.”

The Battle Cry of Freedom. (George F. Root). “We will welcome to our numbers the loyal true and brave, shouting the battle cry of freedom; And although they may be poor, not a man shall be a slave, shouting the battle cry of freedom.”

Lincoln and Liberty. (Jesse Hutchinson, Jr.)“Our David's good sling is unerring, the slaveocrat's giant he slew; Then shout for the freedom preferring, for Lincoln and liberty too.”

Call 'em Names, Jeff. (George F. Root). According to the song, Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard started a propaganda campaign to convince Union soldiers that they were controlled by eastern abolitionists: “They really thought that calling names, had strengthened their position; when all their sneaking curs up north, ran yelping abolition.” The response was unequivocal: “We take the name you gave us, Beau, we mean to make it true sir. We'll first abolish slavery's power and then abolish you sir.”

Good Bye, Jeff. (Philip P. Bliss). An advisor to Jefferson Davis lets him know that the jig is up: “For we got ourselves in trouble with the black man Jeff, now you see we have to give it up and run.” John Brown turns up again – “But the soul of famous old John Brown has not stop'd marching yet, and the last of Southern Chivalry we'll see; When the echo of the Hallelujah chorus, Jeff, finds you hanging on a sour apple tree.” “We'll free your blacks and fight your whites and dig for traitors graves sir; Until there's not in all the land a traitor or a slave sir.”

The Battle Hymn of the Republic (lyrics by Julia Ward Howell, music unestablished). This was a later version of John Brown's Body that you may have sung in church. Ms. Howell wrote new lyrics at the suggestion of a friend who was concerned that John Brown's lyrics about a body moldering in the grave were too coarse and macabre for soldiers to sing. As silly as this notion might seem to us now, the end result was one of the great achievements of American poet: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord, he is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored; He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword, his truth is marching on.” That this was a crusade to end slavery was explicit: “As he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,” and “Let the hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel.”

There is also a nice monument to Generals Grant, Sherman and Sheridan, as well as Secretary of War Edward Stanton, on the Ohio Statehouse grounds. Might be worth a look if you’re in the area.