“There Is No Festival Like This” is the slogan of the FestadoAvante, an annual festival of the CommunistPartyofPortugal (PCP). On September 6-8, 2019, we had the pleasure of experiencing it firsthand in Amora (Seixal), a working-class suburb across the Rio Tejo from Lisbon. Indeed, no other festival in Portugal allows hundreds of thousands of people, many of them young, to come together every year for great music and delicious food (especially classics like the bifana, a grilled pork sandwich, and arroz de marisco, seafood rice) while also taking part in lively debates and massive political rallies. The performances of Bonga, a singer-songwriter from Angola, and JoanaAmendoeira, a fado singer who sang in tribute to revolutionary poet Ary dos Santos, were particularly memorable.

This year’s Festa carried special significance. 2019 marks the 45th anniversary of the “25th of April,” also known as the “Carnation Revolution,” which toppled António de Oliveira Salazar’s fascist dictatorship in 1974. It is also the year of general elections (scheduled to be held on October 6) in Portugal, which, unlike the rest of Europe or the United States, has managed to marginalize the farright. Both the overthrow of old fascism and the prevention of new fascism are proud achievements of Portuguese Communists.

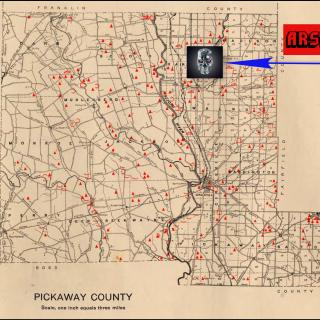

The Communists, who had constituted the largest force of resistance to Salazar, organized many more after the 1974 revolution, especially in the industrialbeltofthemetropolitanLisbonregion and the agrarianAlentejoregion, the breadbasket of Portugal. Look into the archives of bourgeois newspapers, and you can see how the Communists empowered rural as well as urban workers, dramatically changing the economic foundations of politics and culture in Portugal, alarming the powers that be everywhere. “Portugal'sCommunistsHaveCultivatedaRuralRedBelt,” declared the chagrined New York Times in March 1975. How? In another article on the same subject in December 1976, the New York Times explained: “InsouthernPortugal, morethan2,250,000 acres, mostlylargeholdings, havebeenseizedandturnedintocollectivesandcooperatives. . . . In July 1975, the Communists pushed through their agrarian‐reform law, which legalized most of the land seizures and ruled that a farmer could not own land with more than 50,000 points, a system based on type of soil, location and equipment.”

That land reform is probably the most important legacy of the revolution and the Communists’ role in it, which is why the PCP remains strong in the agrarian South of Portugal to this day, according to Rui Pedro Garcia, a third-generation PCP activist whom we met at the Festa, as he was demonstrating the printing press used by the party to print its newspaper Avante! in clandestine fashion during the decades under fascism.

What if similarly radical agrarian reform had been carried out in the United States during or after the Civil War? What if plantations had been expropriated from defeated masters and handed over to freed slaves and other landless workers? What if General William Tecumseh Sherman’s SpecialFieldOrdersNo. 15 had not been reversed by President Andrew Johnson and had instead been generalized to all former Confederate lands? Would not “forty acres and a mule” for all have gone a long way toward cutting the taproot of reaction? If America had undergone “Black Reconstruction,” would it still have a social base for Trumpism today?

The Portugues Communists, though, face challenges of their own. At the national level, their electoral strength peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the PCP-led coalition used to receive overonemillionvotes or nearly20% of the total votes cast. In the post-Soviet era the party’s parliamentary representation was more than halved, hitting the bottom of 6.9% and12 seats in 2002. In more recent years, as the party has been gradually rebuilding its power, new challenges have emerged. Some of the college-educated workers who might have joined the PCP in another era have gravitated toward the LeftBloc. Rui, however, believes that the failure of Syriza in Greece may open some eyes to common weaknesses shared by its allies like the Left Bloc. Secondly, the Socialist Party, which has been forced to depend on the PCP for support to form a minority government since 2015 and therefore also to adopt some progressive measures demanded by the PCP in return (like a higher minimum wage, the reversal of pension cuts, and so on), is claiming all the credit for them, seeking to achieve absolute majority alone and thus be given a “freehand.” Can the PCP strengthen itself while also doing its part to keep the right wing out of government?