Advertisement

To America

Foreword

The idea of The Exercise – cooperation between the country’s two major political parties, on purpose, and why – is fiction, not fact.

Before any fact ever becomes a proven fact, it has a degree of likelihood. When something is proven as fact, it has a 100 percent degree of likelihood. Below that 100 percent, however, lie murky depths, the deeper, the murkier.

The idea of The Exercise has a high degree of likelihood, in large part because fictional Progress Party shotcaller Jack Barns conceived a need for it. No political party can exist in a vacuum.

This brings up an interesting philosophical question: why? Two possible answers: for good, or for evil.

For good? Nope. That really is fiction. There may be room in politics for it, but altruism rarely makes an appearance, by choice or by chance.

For evil? Now, we’re getting somewhere. Behind all the rhetoric, public bickering and inability of elected officials to represent their constituents of every party, or no party, lies the idea of The Exercise.

The idea had its genesis just after the 2016 election of Donald Trump as President. I saw something, watching the political landscape.

The idea of The Exercise appeared, the way sunrise on the prairie appears. But what could be its purpose?

Read the story and get the answer. The Exercise could take place in any similar society in which political parties wield similar powers.

So, to citizens of those lands, I issue a warning: Do not turn a blind eye to how your government runs itself, and why. You need both eyes, squarely on the prize.

That prize is freedom. Freedom is an idea, not words on paper, created by a government. So, like many great ideas, the idea of freedom is itself free, but the citizens – all the citizens, not just the military -- must work and fight to get it, and work and fight to keep it.

Therefore, freedom does not belong to – or is controlled by – any political party, in power or not. Freedom belongs to we citizens.

This story is fiction, but what is not fiction is that American citizens, as well as those from other lands who live in the U.S. and want to become citizens, must continue to act to preserve our freedom, our country, and all the best things she stands for.

Let that be our legacy.

– JB

Preface

Jack Barns was a picture, pushing 5 feet 7 inches in shoes with a one-inch heel. Since his youth, his personality towered over mere mortals who stood taller. His hair had thinned, but he had not gone bald on purpose, as was the fashion for some men. His eyes were black as the coal vein that surfaced in his literal backyard in Toe Share, West Virginia.

His daddy, Elmore Barns, worked 30 years in the mine that he walked to, every morning, right outside the back door. Jack never worked a day in that mine, or any mine, though he knew all about them, what they produce, and what they cost, in men and machines and dollars.

Coal paid for Barns' education, thanks to the coal deposit on the Barns' rocky hilltop. Elmore Barns chose to work his own mine, and he sent Jack to school to learn the business side, for which Elmore had no interest.

In college, Jack Barns used his number-crunching prowess to perform political campaign analyses. He worked a few elections in his four years at university, and was eager for more. After graduation, Barns struck out into the real world. He developed formidable negotiating skills, while selling cars during the summer at his Uncle Ed's car lot.

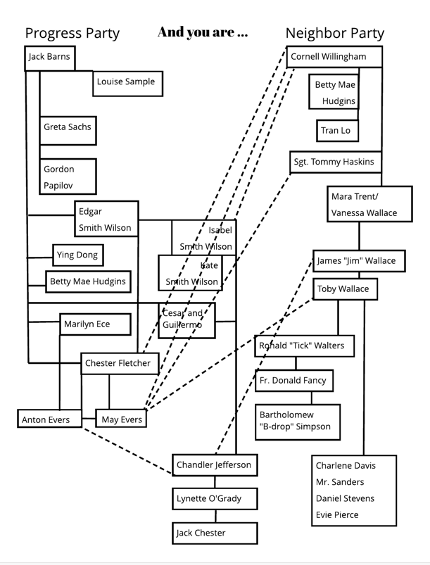

After college, Barns did internships with the Progress and Neighbor parties, the country's two largest political parties. It was during a summer election cycle that he began to shape his destiny with the PP.

Barns became the man in the know, data-wise. The words “a certain percentage” rolled from his lips with ease. This phrase is powerful, when said correctly and backed up with plausible data.

It turned Barns into a shotcaller, because a certain percentage of people listened to him. Though he was a shotcaller, Barns still had bosses who wanted results. Grow the voter rolls, accumulate money and win elections.

Of the three, accumulating money turned out to be the easiest. Political promises have a weight in gold.

Winning elections turned out to be the most difficult. It could be said that winning elections is a matter of money, as in, the party that spends the most usually wins the election.

So, it must follow that winning elections should be just as easy, in the right circumstances.

Nope -- voters are stuck firmly in the middle. And it's not just one voter, but the mass of voters for each party. Voters vote, fat cats spend money and politicians are elected. The day the idea came to him -- the idea of The Exercise -- was an epiphany: no political party can exist in a vacuum. At least one opposing party must exist.

And who makes up those parties? Past analysis had shown that on the voter side, short of a candidate scandal, attraction and retention of voters is a wash between the two big parties.

People switch parties, for a variety of reasons. The undecided remain undecided. Their votes cannot be counted on, only speculated before the vote, and then tabulated afterward.

And those left -- the bloc who left one party to join or vote for the other party’s candidates -- are the real prize.

Results of elections do more than shuffle bureaucrats. Bloc capture increases vote counts, votes identifiable with a candidate's and voter's party. Many government edicts and actions are keyed by voter count by party.

And so, out of this analysis came Barns' idea for The Exercise: to engage in a cooperative venture with the other party for purposes of drawing and retaining constituents.

Champions from within the voter ranks would be chosen by each party, to be seen as an Everyman or Everywoman, but speaking the party line.

Barns headed to his office for a meeting with the PP braintrust. Big, fat raindrops pummeled those on Philly's sidewalks.

The raindrops did their biggest damage at splashdown, spreading out like when a thumb is held on a hose end. Barns ran into his building, and the water cascaded off him onto the entry carpet. He stepped aside and directly in front of the main lobby guard, whom he did not see.

“Take your coat and hat, sir?” he asked. Barns calmly turned, and said,

“You just scared the morning shit out of me. Thank you.”

Barns doffed his hat and coat, which the guard hung on a rack behind a large potted plant. Barns headed to the far bank of elevators, to the top floors. No one else waited there.

The doors opened on the car he called. Empty. He stepped in and stuck in his key to unlock travel to the top three floors, and pressed his floor, the uppermost of the three.

This particular elevator car had a distinctive little “bang” as it passed the floor before his.

Today, it woke Barns from his daydream of The Exercise.

He walked out of the elevator, toward his office at the end of the hall. Louise, there just a year less than Barns, sat at her desk. Louise Sample was petite, which is normal for a woman of Puerto Rican extraction. Like Barns, she, too, stood tall.

“Hello and good morning,” Barns said cheerfully, walking up. Louise handed him his messages and mail.

“If you say so.”

“Ah, what’s wrong?”

“You’ll see,” she said, looking to his office.

He already knew the answer. Inside his office were three of the most powerful people in the country, two men and one woman, collectively, the boss.

They sat in the comfy seats that faced the floor-to-ceiling windows looking out over the city.

“Everybody comfy?” Barns asked.

“Tell him,” said Greta Sachs, PP chairwoman. Sachs retired after 25 years in the U.S. Army, and her organizational prowess did not go unnoticed by the party. Tall, Sachs was an impressive, imposing figure.

“You tell him,” said Gordon Papilov, vice chair. Papilov was the son of an English father and a Russian mother, both spies during World War II. Papilov never said for whom, and no one was asking.

“I’ll do it,” said Edgar Smith Wilson, the party’s first post-war shotcaller but now a hired gun for the PP. Smith Wilson cut the figure of an elegant gentleman, but like many things in this world, it was an illusion.

“We read your report, saved you the trouble of doing it in person. We like the idea and want you to go forward with it,” Smith Wilson said.

“How’d you … Louise,” Barns said, tapping his desk-top phone.

“Louise, did you give them the report?”

“Hot off the press.”

“Thank you very much,” he said, mockingly perturbed.

“How are we even going to start? How do we approach the other party?” Sachs said.

“It’s done,” Barns said. “I have a meeting this afternoon with my opposite number. He already likes the idea.”

“I guess, well, I’ll be the one to say it,” Smith Wilson said.

“If the public finds out, there won’t be a jail big enough to hold us all.”

“We’re a long way from worrying about that,” Barns said.

“Your idea to pump up negative publicity in the media while each party uses a champion, well, it has a hole,” Sachs said.

“The negative media, that’s no problem. Hell, we get that for free, whether we want it or not,” Papilov said.

“What we can’t get, though, reliably, without hiring an actor, is a champion,” Sachs said.

The meeting concluded and Barns was left alone. What he hadn't told them was that he'd already had activity in that area. He was surprised Louise hadn’t volunteered that, too.

His search had begun weeks earlier on a college campus, in the student union. That day, the Asian Student Association had a meeting. Barns sat alone at a table, and an Asian girl, a student, he assumed, sat down.

“You mind? I been on my feet all day,” she said, kicking off her flip-flops and massaging her right foot.

“No, help yourself.”

“Funny,” she said, loud enough for Barns to hear.

“What’s that?” he said.

“You don’t look Asian,” she said, looking up with a smile and a hope he knew what the hell she was talking about. He was only one of three Occidentals – white people – in the large union room.

“Big fan,” he said, stupidly, not getting her joke, but making one of his own.

“Big fan? Of all Asian students, or did you have someone in mind?” she asked, getting the allusion to Big Fan, a fake Asian name. She giggled. He continued to look out over the crowd, hoping his Spidey-sense would direct his eye.

“I say, did you have someone in mind?”

“No, not really,” he said without looking at her.

“I’m looking for someone … to do a job.”

He gazed across the room at the other, some 100 students.

“What kind of job? I might be interested.” That got his attention.

“Really? Well, we need to talk away from here. Here’s my card. Call me later, after the meeting, and we’ll have a chat, okay?” he said, sliding his card in front of her.

On the final day of her vet, Barns learned Ying Dong was a college student, but also a spy in the employ of a Chinese drug cartel.

Then, Barns thought of the Neighbor Party's first champion, who also never did a day on the job. Recruited by NP field personnel, Obie Kendrick, 23, had a nasty habit of the cocaine variety, plus a second nasty habit of armed robbery to pay for it. Just one day after signing on, Kendrick, of Busted Flat, Arkansas, was arrested in a little town in Oregon for armed robbery.

The second Exercise was equally as disastrous. The PP selected a woman from Texas. The life and times of Miss Betty Mae Hudgins, 40, of Houston, Texas, read like an Old West novel.

Hudgins ran away from home when she was 10. She wound up in Houston, and worked a variety of jobs, including restaurant hostess, waitress and cook, carpenter, road crew flagman, and others. A Houston reporter once called those other jobs, “the kind that never land on a lady’s resume.”

She sued the paper for defamation of character for that article, and won a handsome sum. She then parlayed her entire fortune to purchase a failed chain of laundromats in the Greater Houston area, turning them into nightclub-laundromats.

It took her just four years to go from three to 13 locations.

Twice voted the most eligible bachelorette in Houston, Hudgins, an African-American, became a local hero.

But, she was not a good businesswoman. Just before the PP began talking to her, Hudgins hired an accountant who proceeded to rip her off, at the height of her celebrity and business success.

She discovered the theft – $20 million – but was able to cover it up with a series of money-laundering projects for local businessmen whose monogram is M.O.B.

Barns wasn't worried about that when he recruited Hudgins. Exercise #2 was shut down after Hudgins was convicted of tax evasion in Dallas federal court.

A number of phone calls and promises Barns never intended to keep kept Hudgins' story from reaching any media outlet, despite her celebrity.

Hudgins’ Neighbor Party counterpart was Tran Lo, from Laos, a boat person who came to America in the early 1970s. Lo was a diesel mechanic.

He found work easily in the U.S., working first for the Greyhound Bus Line, and others. When The Exercise #2 found him, he was working for a cab company in Downtown Philadelphia.

While test-driving a cab, Lo saw Neighbor Party shotcaller Cornell Willingham, flagging him down. Paunchy, balding and graying, Willingham looked older than his age, which he did not know for certain.

Growing up in the post-Depression South, Willingham and his mother skipped from camp to camp, and place to place, and back to nowhere, again and again.

A defining moment came one evening, when Willingham wandered into a gas station near the camp.

The station man, Estill Music, looked down. “Whatchoo want here, boy?”

“Just fixin' to buy a Coke, please, sir,” Willingham said, handing over a nickel.

“A nickel, huh? I don't sell no half-Cokes,” Music said.

“That's all I have, sir.”

“Well, then, I guess you need a job, so's you can pay me the other five cents,” Music said.

“Yes, sir,” Willingham said. “When do I start?”

Music, the Neighbor Party's first shotcaller in the post-WW II era, became Willingham's mentor. Willingham was thinking about Music as he flagged Lo down.

After Willingham got in the cab, Lo told him he was a mechanic, test-driving, but he didn’t have the heart to just drive by.

It was then that Willingham recognized Lo did have a heart, as a candidate for The Exercise.

To get the ball rolling, Willingham persuaded Lo to start an association of immigrants who’d made good. Within a short time, a kind of international chamber of commerce came into being. New citizens, eventually including Lo, made up a large part of the group. All loyal to the Neighbor Party, Willingham had a corps of champions.

But The Exercise #2 was a lop-sided failure. Lo made good efforts and had great results. Hudgins was a closeted skeleton just waiting to be discovered, so the decision was made to shut down The Exercise.

Over lunch one day, Lo told Willingham that he felt frustrated. Had he done any good?

“Of course,” Willingham said. “The people saw someone -- that’s you -- who had, not just the desire to be free, but the desire to work for a living. It's an interesting connection.

“Having the desire to be free is one thing, but what you have to do, once you come here, is something else, entirely. You have to live.”

The two men talked about America. Willingham told Lo that getting people to work together sometimes drove them apart.

“No, Mr. Willingham, I do not believe that,” Lo said.

“What drives them apart is themselves, individually, not as a group. That may be the only downside of being able to recreate oneself as an American.

“Individualism and independence seem to be made for each other, but they also seem to keep people apart, once we’re all together.”

A few days after that conversation, Willingham told Barns about it. Lo's words now rang in Barns' head. Barns felt the need to check in with Willingham, his NP counterpart. Their future needed discussion.

“Cornell, it’s Barns.” Willingham was in his office.

“Jack, what can I do for you?”

“I was thinking,” Barns said.

“Oh, geez, now you went and done it.”

“Very funny. I was thinking about The Exercise, if we’re going to do another one,” Barns said.

“Well, we’re both still here.”

“It never really had a good trial,” Barns said.

“Jack, come on. Once the curtain goes up, we play our parts. We’re all still part of the same acting company, right?” Willingham said.

“Right.”

“As for the next Exercise, I think we just need to wait for another opportunity,” Willingham said.

“Something will come up.”

End serial 1

Copyright © 2018, 2019 Published by Jef Benedetti jefbenedetti@hotmail.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, contact the publisher by email, with the subject “Request Use Permission.”

ISBN 978-0-9801372-2-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018909114

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. First edition.