Advertisement

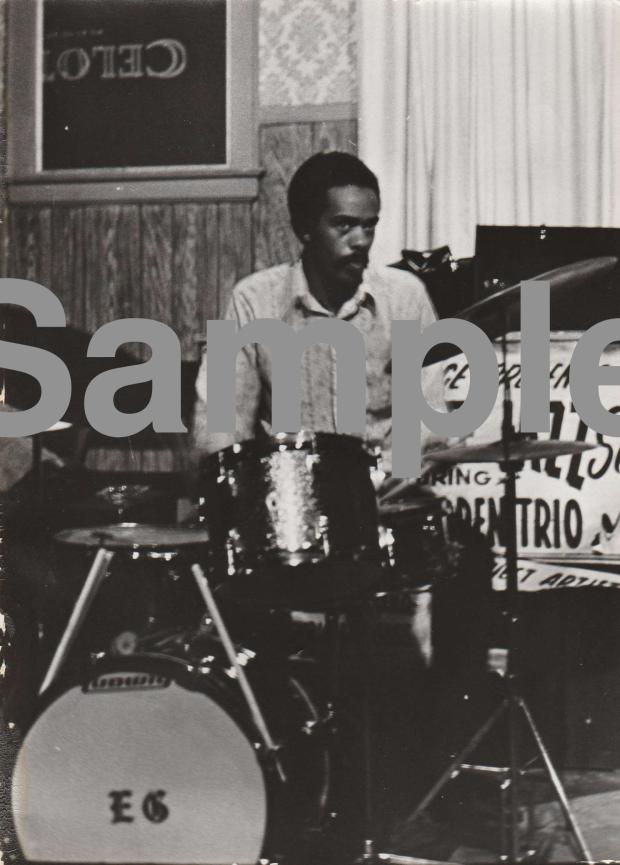

Take Five with Jazzmary Daniels

I saw 63 year-old Tommy Smith play at Dick’s Den a couple weeks ago. His drumming matched what he told me on the phone Sunday: “I’m a Bebop drummer. That’s where I come from.” Tommy Smith comes from the South side of Columbus originally and has been a lot of places.

In the 1950’s, he started playing with his grandfather in the Elk’s Lodge Marching Band, and fell in love with jazz after going to shows with an uncle at the Palace Theatre downtown.

During the 60’s, the teen Tommy was living on the West side, attending Central High School and becoming part of small city-wide jazz community.

“In high school, in Columbus, there were a bunch of us,” Smith said. “Not a bunch…I would say we were the young lions. And we were all into Jazz.”

Tommy and his friends would go to Columbus jazz spaces such as The Regal on Long Street, The Copa on Mt. Vernon, The Cadillac Club, the Starline and the 502 on St. Clair.

At the 502 they would watch greats such as Miles Davis and Horace Silver during Sunday matinee shows.

Tommy recalled the dream.

“I walked all the way from the West side. Just to watch them walk in, carry their gear in the club. And then I would just walk on home. Just to look at them, and say: ‘I can’t wait to do that.’” Two of Tommy’s young lion buddies, Fred Thomas and Warren Stevens played at a coffee shop called the Sacred Mushroom on campus. It was a place where touring musicians would frequent after the clubs.

“I had a chance to sit in with Wes Montgomery when he was in town, and all the musicians that came in town,” Smith said of the Sacred Mushroom jam sessions. “So the younger musicians had a chance to see these people.”

After High School, Tommy played Columbus clubs and a touring circuit that allowed jazz musicians to earn a living playing six nights a week until meeting, Chino Feaster, a Brooklyn organ player who offered him a job playing ski resorts in New York.

Feaster sent Tommy a plane ticket and he moved to Brooklyn in the late 1960s. “I still got the ticket stub. 17 dollars,” Tommy recalls. “One way. Can you imagine that? TWA. “

Tommy moved in with Feaster in Brooklyn and they earned money playing at resorts in upstate NY, Maine and Vermont.

As a burgeoning jazz talent, Tommy decided he needed to stay on the East Coast to see what could happen for him.

“I made up my mind,” he said. “After this ski season is over. You ain’t gonna be skiing in no summer time. I didn’t know what kind of gigs you were gonna have.”

So Tommy saved his money and got a spot in New Jersey. He ended up playing with a bunch of local cats in Newark, NJ, which helped him hone his skills and relationships.

“Once I moved over there in Newark, New Jersey, and East Orange, this drummer knew Rahsaan. So he took me past his house. That’s how I met him. I never did meet him in Columbus. I knew of him. I never even seen him play.”

After meeting Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Tommy eventually got a call from the jazz legend. “One day he called, and he said 'what are you doing?’ ‘I said not, nothing.'”

“He (Rahsaan) said, 'I’m going to Atlanta. Do you think you can play?' I said, 'yeah.'”

This call led to on and off gigs with Kirk.

“Then he called me again and asked me to go to Europe,” Tommy continued. “He said, 'get a passport.' And that’s how all that happened. So I played off and on. He was kind of difficult to work with. Some guys are like that. I don’t know what it is. And I’ll take it for a while. And then I would quit. And then he would call back again. I guess he understood because he called back again.”

Tommy played in New York for years at places such as St. Nick’s Pub, Lennox Lounge, the Vanguard and places he referred to as “mob joints” in Staten Island until moving back to Columbus in the late 1980s. “We weren’t making any money,” he said. “Them old raggedy apartments. Sixty bucks a month, all the rats you could watch.” Tommy quipped on his NY living conditions that eventually brought him home.

“I put music on the back burner. Only reason I left New York is that I wasn’t making no headway. I gave myself 20 years.”

He worked nobly in Columbus as a Social Worker for 25 years helping troubled juveniles in group homes until recently.

“I’m retired now. So I don’t have to answer to no body.”

Tommy Smith can focus on Hard bop again now that he has some free time.