First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s

First Black Public High School

by Alison Stewart

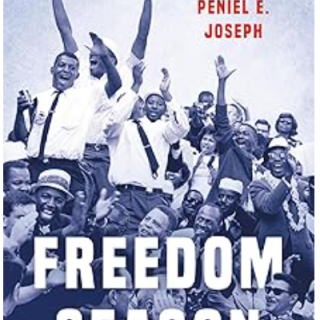

During the 1880s through the 1950s–what the African American historian Rayford Logan called “the nadir of American race relations,” when the striving of blacks was met by the iron fist of white supremacy–America’s first black high school became the springboard to almost a century of black achievement.

In 1870 with some public money, a small legacy from Myrtilla Miner, a white leader in educating poor black women, and the prodigious efforts of Washington’s black elite, the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth held its first classes. After bouncing around to various locations, Congress appropriated $112,000 for a permanent structure, and the M Street School was opened to black students in 1892. A number of its earliest teachers had been trained at Ivy League schools, studied abroad or held advanced degrees. Because of Jim Crow, they were often unable to find work in their chosen fields, and so migrated to Washington, D. C. and the M Street School, which was renamed Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School in 1916.

It was during the tenure of the great black feminist Anna Julia Cooper that the school went from being a diamond in the rough to a magnificent jewel. According to Stewart “Her goal was to build a solid classical curriculum that would be rigorous, challenging and on par with the courses of study at white schools in the District.” Cooper succeeded far beyond the white establishment’s expectations. Graduates of M Street School attended Harvard, Cambridge, Dartmouth and Brown. Cooper also ensured that students of few means were able to attend and succeed at M Street school also. By the time she was forced out in 1905, Cooper had left a huge imprint in the field of education in Washington, D. C.

Dunbar was not only a high school, it was a safe haven for thousands of black children. It was here they learned that they were as good as anyone else and that they should strive for excellence; it was here to a certain extent they were protected from the harshness of segregated Washington, D. C. Students at Dunbar did not have time to dwell on racism in American society; they seldom interacted with white people. (There is a hilarious story from a Dunbar alum who was so curious about white students she decided to walk through a white neighborhood on her way to school so she could see what white students were like!) Expectations for students were very high, and woe to the student who failed to meet them. And yet during its first eight decades Dunbar turned out graduates who went on to become civil rights leaders, educators, authors, high ranking military officials and firsts in their fields of endeavors.

The death knell for the special place that was Dunbar was Bolling v. Sharpe, a 1954 school desegregation case. In a unanimous decision the Supreme Court stated that black students in the racially segregated D. C. school system were denied their rights to due process under the Fifth Amendment. The all-black environment at Dunbar was in part what made it special, but it had been ruled unconstitutional. The irony is that one of the leaders in the fight against segregated schools was the attorney Charles Hamilton Houston, graduate and valedictorian of the class of 1911.

The changes that swept through American society in the 1950s and 1960s impacted Dunbar High School too. Desegregation and the concept of neighborhood schools changed the demographics of the student body. No longer were the majority of Dunbar students the progeny of strivers or strivers themselves; the school was now populated with children whose families were part of the Great Migration and the urban poor; many were ill equipped to handle the rigors of Dunbar. Long time teachers, many of them steeped in the self-help philosophy of the school’s early years, retired or died. Those who remained clashed with new faculty who tried to modernize the school and its curriculum and old alums who were determined to maintain the Dunbar of their youth. Discipline became harder to maintain and academic standards slipped. Parental involvement plummeted, and drugs and violence came to Dunbar. By the 1970s Dunbar had become just another troubled urban school with an uncertain future.

Alison Stewart, an award winning journalist and graduate of Brown University, writes passionately about the school in First Class. (Her parents are graduates and met and fell in love there.) Yet First Class is not just about Dunbar High School and its many famous former students; it is an historical record of race, class and public education in America in general and Washington, D.C. in particular. Stewart also does a fine job of explaining how local and national politics drove so much of what was and was not accomplished at Dunbar.

As of the publication of First Class, a new Dunbar High School is being built. Alums, architects, planners, public officials and educators are trying to ensure that the new Dunbar is a reflection of its glorious past, and hoping they can replicate its historical success of excellence and uplift. They all realize that merely erecting a new building will not ensure Dunbar’s greatness, but they also know it is a start. And they are cautiously optimistic.

Dr. Marilyn K. Howard earned her PhD in American history from The Ohio State University (Dissertation: Black Lynching in the Promised Land: Mob Violence in Ohio 1876 - 1916). She is an associate professor in the Department of Humanities at Columbus State Community College. She has published essays in a number of anthologies, including the Encyclopedia of Racial Violence in America and the Encyclopedia of Jim Crow. She continues to conduct research on the lynching of black men by white mobs in Ohio.