Advertisement

Columbus is in the middle of a building boom. Sleek apartment towers climb skyward, marketed with rooftop lounges and pet spas. Rents stretch past $1,500 for one-bedroom units. But a very different Columbus exists on the other side of the leasing office glass: one where families tuck their children into bedrooms streaked with black mold, where winter nights are endured with broken furnaces, and where cockroaches scurry across kitchen counters.

These tenants aren’t silent. They are doing exactly what the city says they should — calling 311, filing code complaints, and showing up in Environmental Court. Since January 2024, Columbus renters have filed more than 7,000 housing complaints, and the court has opened nearly 2,600 cases. Judges have ordered more than $1 million in fines against landlords.

Yet the same addresses keep appearing in 311 logs, the same landlords keep showing up in court dockets, and the same families keep waiting for repairs that never come. Columbus’s enforcement system documents the crisis in detail, but rarely fixes it.

Thousands of Complaints, Few Consequences

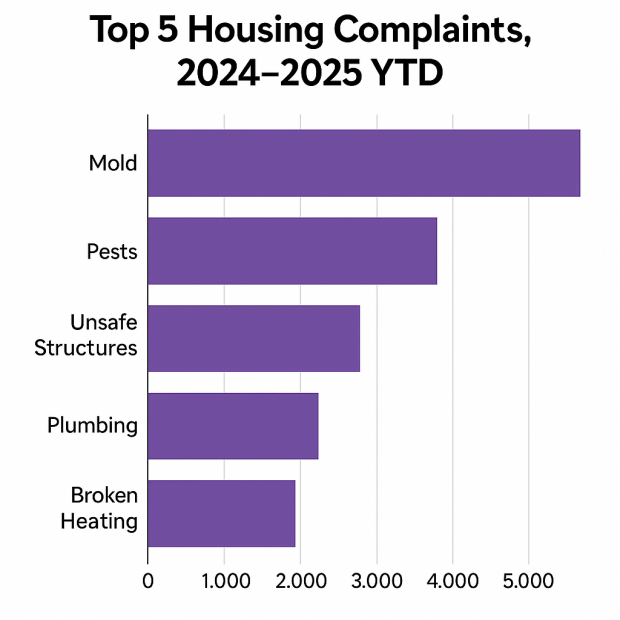

The city’s 311 system is the front door for tenant complaints. In 2024, it recorded more than 7,000 calls about unsafe housing conditions. The leading issues: mold, pest infestations, broken plumbing, unsafe structures, and heating failures. (see graph at end of story)

But complaints don’t equal solutions. Fewer than 10 percent of cases led to enforcement orders. The majority were marked “closed” after an average of 37 days — often with little evidence that anything had been repaired.

A Docket Full of Repeat Offenders

Behind the numbers are landlords and property companies that show up again and again. Environmental Court filings from 2024–2025 reveal a handful of chronic violators dominating the docket:

- Charmaine Macklin — 36 cases

- 2000 Fulton Property LLC — 30 cases

- Carriage House Ohio LLC — 24 cases

- Grupo Sanchez LLC — 24 cases

- Brinson Properties LTD — 21 cases

In 2024, the court logged 1,695 cases. By mid-2025, 884 more cases had been filed, but only 179 closed. The backlog is growing, and the same names keep surfacing.

Fines Add Up — And Mean Little

The Clerk of Courts reports that from January 2024 through July 2025, the Environmental Court disbursed $937,537.52 in civil fines and $86,248.54 in criminal fines. In total, more than $1 million in penalties.

But for landlords with portfolios of dozens or even hundreds of rental units, those fines are little more than overhead. Many simply treat them as the cost of doing business — paying penalties while continuing to rent unsafe housing.

Tenants Left With Few Tools

For renters, the last resort is rent escrow — paying rent into court until repairs are made. But records show escrow is slow, confusing, and opaque.

In 2024, renters filed 285 escrow cases; another 139 were filed by mid-2025. The median time to resolution was 82 days. Some stretched beyond a year. Most were resolved under vague “other termination” categories, leaving little public record of whether landlords made repairs or tenants ever saw justice.

The City’s Defense

Confronted with the data, Columbus officials argue that the city is taking affordability and enforcement seriously.

“The City of Columbus is prioritizing housing affordability through multiple tools,” said Christine Reedy, a public relations specialist with the Department of Development. She pointed to voter-approved affordable housing bonds, affordability policies, and partnerships with nonprofit and private developers that have “supported the creation and preservation of thousands of affordable units across the city since 2019.”

Reedy said the city regularly reviews market data — permits, affordability requirements in development programs, and third-party studies — to monitor production across income levels. She noted that programs such as emergency and critical home repair funds and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit help property owners bring substandard housing up to code, though participation “varies depending on the type and size of the property.”

Asked about proactive rental licensing — requiring landlords to certify units before leasing — Reedy responded that while the city already enforces housing and building codes, “any new approaches would require thoughtful consideration by the administration, City Council and community stakeholders before moving forward.”

As for the influence of powerful industry groups like the Columbus Apartment Association, Reedy said no single entity drives decision-making. “Housing policy is developed in consultation with a broad range of partners — residents, community organizations, housing advocates, nonprofit developers and industry groups,” she said. “The city’s focus remains on ensuring safe, stable and affordable housing for Columbus residents.”

A Two-Tier Housing System

The Department’s answers highlight an undeniable tension. Columbus is building more — thousands of new units, many subsidized with city-backed bonds — yet the city’s own data shows thousands of renters remain stuck in deteriorating units, filing complaints, waiting months for repairs, and watching the same landlords cycle through Environmental Court.

The vacancy rate in high-end apartments now hovers around 12 percent, according to the Columbus Apartment Association. Working families, however, are still competing for scarce affordable homes, often in poor condition.

The Cycle Without End

Tenants complain. Inspectors cite. Courts fine. Landlords pay. And then it begins again.

Columbus officials say they are working to expand affordable housing. But until enforcement gains real teeth — through escalating fines, proactive inspections, and stronger tenant protections — thousands of renters will remain stuck in unsafe homes, paying for a system that protects everyone but them.