The City of Columbus, high-end developers, and mining companies have been hoarding local quarries for two centuries. Now one of Columbus’s last remaining quarries – which is not surrounded by high-end development or a fake metro park – will remain a dumpster of sorts, even though a Native American burial mound could be on a small island in the middle of its rain-filled crater.

In the 1800s, thousands of Italian immigrants flooded into the near west side of Columbus to make $1 a day hacking out limestone with pickaxes and were often beaten by their Upper Arlington bosses if they slacked. Many decades later, after the limestone was extracted, the quarries turned into lakes from rainfall, sold to developers, and ringed with high-end developments, such as at Runaway Bay.

Developers are sly at keeping coveted land and designs for coveted properties a secret. Intriguing is how the quarry on McKinley Avenue was spared from rich people’s condos. But it suffered a worse fate back in the 1970s when the City chose to dump residuals filtered out of local drinking water treatment plants, such as alum and lime, into its water.

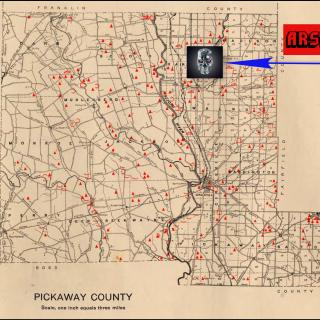

Given the acronym “MAQ” (McKinley Avenue Quarry) by the Division of Water, the quarry is a half mile in length and surrounded by a tall fence and bushes. Currently, a thick green and yellow foam rests on top of its northern half.

Albeit during a different era, the decision to pollute the quarry and its lake was another insult to Native Americans and those ancestors who lived on these high grounds above the nearby Scioto River for 15,000 years, if not longer. Standing stoically on the edge of the MAQ is Shrum Mound, one of region’s last remaining conical Native American burial mounds. The Ohio History Connection believes it was constructed by the Adena people 2,000 years ago and possibly an homage to a distant mountain (pictured above upper right).

Ohio has learned much about Native American mounds and earthworks during the 25 years state historians worked to earn UNESCO’s World Heritage status in 2022. Mind-bending is how those mounds that are in close proximity to each other, such as the Octagon and the Great Circle in Newark, are connected to the heavens through alignments to the moon or sun. Signifying that mound complexes are ceremonial grounds.

What shouldn’t come as a surprise then is how an Ohio University graduate student believes Shrum Mound may not be alone.

In the middle of the MAQ could be another burial mound on an island which logically shouldn’t be there, said OU’s Alex Armstrong who studies land uses of Ohio Valley native earthworks sites post-colonization. Most times the island, which appears to have a roundish top, is covered in egrets, herons and cormorants, and aptly named “Bird Island” on older maps of Columbus (lower picture in above collage).

“What I did do was to hike up the Shrum Mound in the winter and check the island out through binoculars,” said Armstrong. “I’ve done a lot of searching for mounds in the woods over the years, and what I saw with the leaves all down sure looked like it could be.”

Armstrong said he had heard of the MAQ (ghost) mound from an amateur historian.

“There has been so much careless destruction of mounds and other cultural sites over the years, but every now and then you find a really cool story of somebody taking the initiative to save one,” he said. “It would be a very cool story, but by no means unbelievable, if some quarry manager way back when had managed to get the mound spared.”

Also, a story of atonement in some ways considering how greedy and tyrannical the quarry bosses could be – if Bird Island is an actual burial mound.

Nearly two-centuries later, the City of Columbus is preparing to spend tens-of-millions to dredge the MAQ because it “has limited remaining service life under the current disposal rates of residuals,” as stated by an Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) review of the project. The Ohio EPA also stated a new “dewatering facility to thicken, dewater, store, and handle all or some of the residuals produced” will be built near the MAQ.

The $46 million project is necessary considering the Division of Water serves 1.2 million customers and is growing. The City operates three large interconnected water treatment plants: the Hap Cremean Water Plant, Dublin Road Water Plant, and Parsons Avenue Water Plant. It transfers the liquid residuals to the MAQ through sludge lines. The Columbus annual residential water bill is approximately $544, and the MAQ and other projects are expected to increase the bill to $665, as stated by the Ohio EPA.

“The quarry is getting full and in order to continue to treat water for our growing region we need to make room in the quarry,” stated Division of Water assistant administrator Matt Steele in an email to the Free Press. “We are planning on dredging approximately the same amount of residuals we send to the quarry every year so the quarry won’t have a net gain or loss of residuals. We will dredge the residuals with a floating dredge and send them to an onsite dewatering facility to be dewatered.”

Some good news for rate-hiked customers is how after the residuals are dredged from the MAQ, they will be recycled for agricultural purposes, among other beneficial uses, says the Division of Water.

More good news is that “Bird Island” will not be touched.

“The dewatering facility will be constructed on land, the dredging operation will be in the water, and neither will impact Bird Island,” stated Steele. “Current city staff have no knowledge of a burial mound on Bird Island, and those from the 1970s when the quarry was purchased by the city are long gone.”

But questions will linger...Will the City or someone else end the mystery of Bird Island? And if it is a burial mound – during a time when the First Nations are demanding more respect for the remains of their deceased ancestors – what then?

Would you want your ancestors’ place of burial surrounded by a green and yellow foam?

The Ohio History Connection told the Free Press it does not have any records of burials on the quarry site known as Bird Island.